Anatomy of a Scandal on Netflix has gripped audiences via its depiction of a sexual assault accusation against Britain’s ‘most fanciable’ minister. James Whitehouse (Rupert Friend) faces trial for allegedly raping Olivia Lytton (Naomi Scott), a former staffer with whom James had a five-month-long affair.

Whitehouse’s political career and marriage to Sophie (Sienna Miller) hang in the balance as Kate Woodcroft (Michelle Dockery), the prosecution counsel, strives to convince a jury to convict James.

Director S.J. Clarkson adapted Anatomy of a Scandal from Sarah Vaughan’s best-selling novel of the same name. Sarah Vaughan drew writing inspiration from two-real life British scandals, which we’ve detailed below.

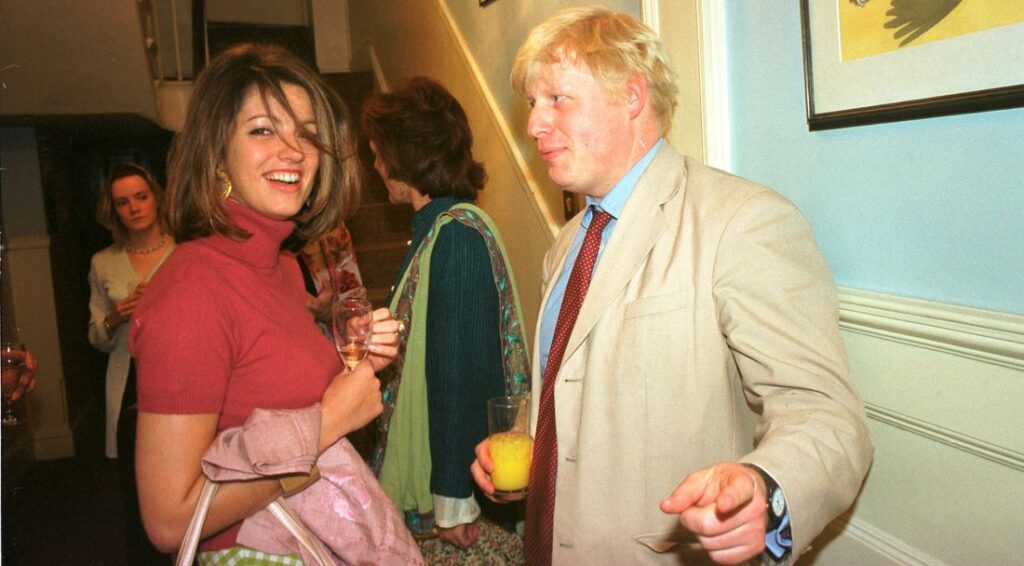

The first scandal involved Boris Johnson’s lie about having an affair with columnist Petronella Wyatt

In 2004, Tory frontbencher Boris Johnson was accused of having an affair with columnist Petronella Wyatt. Boris denied the affair but later admitted to it after Wyatt’s mother claimed that Wyatt got pregnant during her dalliance with Johnson.

Johnson had sensationally described the affair as an ‘inverted pyramid of piffle.’ Johnson lost his position as party vice-chairman, not because of the affair but because he lied about it.

“This is nothing to do with personal morality,” a politician told The Guardian. “Last weekend when all this came up Michael stood by him and said shadow ministers can live their lives as they want, it was not a matter for him. It is a matter for him when shadow ministers don’t tell the truth.”

In an interview with The Guardian, Sarah said she was surprised at Johnson’s nonchalance about the scandal. “There was a lot of flummery and flannel; lots of chuntering and ‘all chaps together’-ness about it,” Vaughan told The Guardian.

“He confirmed the story was true and didn’t seem to express any remorse. It was the first time I was aware of a public figure admitting to lying and not seeming to be bothered by it.”

Vaughan said she didn’t base James Whitehouse on Boris, but she incorporated Johnson’s approach to the truth into the narrative.

“As Theresa May put it in the Commons recently, either he ‘didn’t read the rules, or [he] didn’t understand them, or [he] didn’t think they applied to [him],’” Sarah continued.

“I told the truth, near enough. Or the truth as I saw it,” James Whitehouse says in the series.

The second scandal involved the treatment of Ched Evans’ rape accuser

In Anatomy of a Scandal, the defense counsel tears Olivia Lytton’s testimony apart, asking questions about the intimate details of her sex life. During Ched Evans’ retrial on a rape charge in 2016, the judge controversially allowed evidence about the complainant’s sexual preferences.

Ched Evans was convicted of raping a 19-year-old woman in a hotel room following a night of heavy drinking. The appeal court offered Ched hope by admitting new evidence and granting Evans a retrial.

Following an eight-day retrial, it took two hours for a jury to acquit Evans. Women’s campaigners and support groups expressed their displeasure at the court’s interrogation of the complainant’s sexual behavior.

“This will set a precedent in rape cases to follow where defence barristers will comb through an alleged victim’s sexual past and following the alleged assault at a time when they are suffering trauma,” a feminist activist told The Guardian.

Vaughan was similarly distressed by the accuser’s treatment by the press and the effect the case might have on women coming forward to report sexual assault. She told Exploring Exeter:

“I was upset by the way in which the alleged rape victim was depicted by commentators and started thinking about how horrific it must be to summon up the courage to come forward with a rape conviction and then have doubt cast on that in the papers and in court.”

The Libertines Club depicted in the series mirrors a dining club at Oxford University

In Anatomy of a Scandal, James and Prime Minister Tom Southern belonged to a debaucherous fraternity known as the ‘Libertines Club.’ Collins dictionary describes a Libertine as ’a person who is morally or sexually unrestrained.’

The members of the fraternity and its supporters defended the boys’ promiscuity and drug use by saying, ‘boys will be boys.’

The fictional ‘Libertines Club’ mirrors the Bullingdon Club in Oxford, which was founded as a drinking club and later became a drinking and dining club. It consists of the sons of the politicians, the nobility, and the wealthy.

Members of the Bullingdon club are famous for wild partying and reckless destruction of property. One woman told The Guardian that Bullingdon members ‘found it amusing if people were intimidated or frightened by their behavior.’

Past members of the club include Boris Johnson, former Prime Minister David Cameron, and King Edward VIII.

Vaughan likely crafted the ‘Libertines Club’ from her experiences with Bullingdon club members during her time in Oxford. “I obviously merged concerns I’d had about power, perceptions of truth, privilege—all seen at Oxford and in Westminster—and consent,” she said.

S.J. Clarkson adapted the book to spark conversations about power, privilege, and entitlement

S.J. Clarkson said that she devoured Sarah Vaughan’s book in a day and a half. She saw beyond sexual assault and into themes such as wealth, privilege, and entitlement. Clarkson said:

“I started to ask myself questions, too, about whether the real ‘scandal’ wasn’t just the alleged assault of a young woman by her powerful boss in a House of Commons lift. But really, more broadly, about wealth, privilege, entitlement and men raised to believe they own the world.”

She pushed for its adaptation into a small screen production primarily because she knew it would spark conversations about contemporary issues. She explained:

“I saw it would divide people and get them talking about some of the biggest issues of our day. From a director’s point of view, it had the lot.”