When Genie Wiley and her mother mistakenly walked into a Los Angeles County welfare office, the child’s appearance petrified everyone present. Genie stooped and walked like a rabbit, couldn’t control her bowel movements, and had a rare dental condition that caused the growth of two sets of teeth. Many suspected autism, but a deeper investigation uncovered gruesome horrors.

Genie – a fake name given to hide her identity – had been the subject of abuse at the hands of her father for more than a decade. Her insane father had kept her in isolation since she was 20 months old, apparently believing that she was mentally retarded. Every attempt by Genie to make a noise met stern punishment and rebuke.

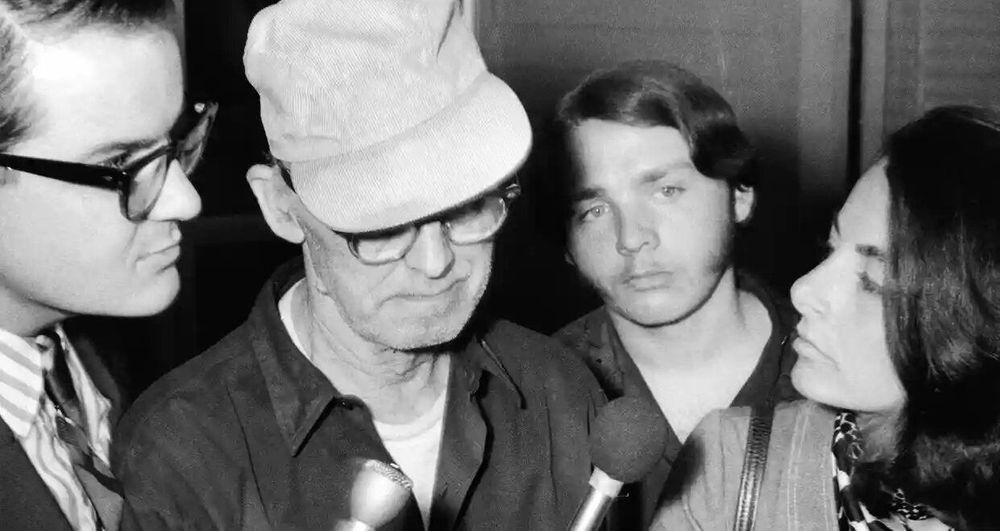

The location of the over 60-year-old Genie remains a closely guarded secret

A year after Genie’s discovery, she was placed under the care of foster parents David Rigler and his wife Marilyn. For five years, the National Institute of Mental Health funded her stay with David before withdrawing funding due to mismanagement of the case. The Riglers ended their care for Genie, later stating in a 1994 NOVA documentary that they assumed that the foster care arrangement was ‘temporary.’

Genie’s placement in foster care homes proved detrimental to her development. In 1977, she detailed in sign language how one of her foster parents punished her for vomiting. Despite this, she returned to foster care until she turned 18, when authorities placed her in an adult care home. The name of the facility is unknown, and the private foundation responsible for her care refuses to divulge the information.

Irene Wiley, Genie’s mother, obtained legal guardianship for her daughter, but Genie had already been placed in a home. Russ Rymer, a journalist, painted a bleak picture of Genie’s condition during her 27th birthday. He wrote:

“A large, bumbling woman with a facial expression of cowlike incomprehension… her eyes focus poorly on the cake. Her dark hair has been hacked off raggedly at the top of her forehead, giving her the aspect of an asylum inmate.”

Jay Shurley, a professor present at Genie’s 29th birthday, offered a similarly somber assessment: “It was heartrending.” Attempts to contact Genie are routinely rebuffed by authorities. The Guardian received the following response after asking to see Genie:

“If ‘Genie’ is alive, information relating to her is confidential and it does not meet the criteria of information that is available through a PRA Request. We would suggest that you contact Los Angeles County with your request.”

Mental health authorities didn’t reply to a query sent by LA County. Susan Curtiss, a UCLA professor who formed a bond with Genie, has similarly been unsuccessful in her attempts to contact or see Genie. Curtiss is, however, confident that Genie is alive. She told The Guardian that the last time she saw Genie was in the 80s:

“I am not in touch with her, but not by my choice. They never let me have any contact with her. I’ve become powerless in my attempts to visit her or write to her. I long to see her. There is a hole in my heart and soul from not being able to see her that doesn’t go away.”

Wrangles between scientists and Genie’s caregivers led to withdrawal of funding for her care

Genie’s appearance from the blue baffled and excited scientists at the same time. The scientists had a specimen that they could use to test the 1967 Lenneberg theory that claimed that children couldn’t learn after puberty. They put Genie through brain scans and countless tests to try to understand Genie’s cognitive abilities.

However, some saw Genie as more than a science experiment – as a human being in need of love and care. And then there were the outliers, like Jean Butler, a rehabilitation teacher who saw in Genie an opportunity to gain fame. Eventually, the caregivers and scientists pushed aside Jean Butler and saw Genie make a stunning recovery.

Genie learned to play, dress, and enjoy music. She sketched pictures, learned words, and sign language to communicate. She also performed admirably in intelligence tests. Susan Curtiss told The Guardian:

“Language and thought are distinct from each other. For many of us, our thoughts are verbally encoded. For Genie, her thoughts were virtually never verbally encoded, but there are many ways to think. She was smart. She could hold a set of pictures so they told a story. She could create all sorts of complex structures from sticks. She had other signs of intelligence. The lights were on.”

Genie started to attend nursery school, further broadening her vocabulary. However, the wrangles between scientists about the best course for her care and development caused inconsistencies in her records, forcing the National Institute of Mental Health to withdraw funding.

In 1979, Irene Wiley sued the hospital and her children’s caregivers for allegedly using Genie for ‘prestige and profit’ and excessive testing. The suit was settled in 1984, and Susan Curtiss, perhaps the most innocent caregiver of them all, was banned from seeing Genie. “Genie had so my losses, and here she was losing the one person who had remained in her life ever since I met her,” Susan told ABC News.

The widely accepted conclusion is that Genie’s scientist caregivers failed her, all except for Susan Curtiss. Harry Bromley-Davenport, a filmmaker who extensively interviewed Susan Curtiss, told ABC News:

“Susie is the only absolute angel in this whole horrifying saga. She is an extraordinary person. The greatest tragedy was Genie being abandoned after all the attention. She disappointed the scientists, and they all folded their tent and left when the money went away – all except Susie.”

Genie’s family suffered tragic fates after the saga ended

Genie’s father, Clark Wiley, never wanted to have children, but after marrying Irene Oglesby, the children came – and died. Their first baby died after being left in a cold garage and the second from birth complications. The third child, John, survived but suffered under the care of an abusive further. He fled home to live with his grandmother, who died in 1958 following a tragic accident.

John returned home to find a little sister, Genie. His grandmother’s death seemed to unlock a new level of cruelty in Clark. He locked Genie in a lifeless basement, and when he came to feed her, he beat her every time she made a noise. John endured regular beatings from Clark, including blows to his testicles inflicted to make him sterile.

Clark, in a move of extreme cowardice, killed himself before his trial. “The world will never understand,” his suicide note read. “Be a good boy, I love you,” Clark wrote in a second note addressed to John. In the aftermath of Genie’s discovery, authorities neglected John and the struggles he went through. Frank Linely, the detective in charge of the case, told ABC News that it was a mistake to ignore John:

“John was as much a victim of the family dynamics as the younger sister was. But he was so little a part of the direction of the case. Unfortunately, we never really paid attention to him. The case comes back to haunt me.”

John left the Los Angeles area for rural Ohio and only saw his mother once before her death in 2003. After the death, he shunned everything to do with Genie and his family, but he can never completely forget it. “I have forgiven, but I can’t forget,” he said.

Despite his father’s best efforts, John ended up having a daughter with his wife. “I was afraid to have kids because of my upbringing,” he said. His daughter turned to crack cocaine for solace after John’s marriage with his wife ended. She was, consequently, unable to take care of John’s two granddaughters. However, John told ABC News that he still retains optimism:

“They didn’t give me the tools, the knowledge about accomplishment and setting goals and the Bible and God. I feel at times God failed me. Maybe I failed him. But it’s never too late.”